The Eight Limbs of Yoga towards Enlightenment

- January 24, 2018

- Posted by: admin

- Category: Featured Content,

By Dr Chandra Nanthakumar

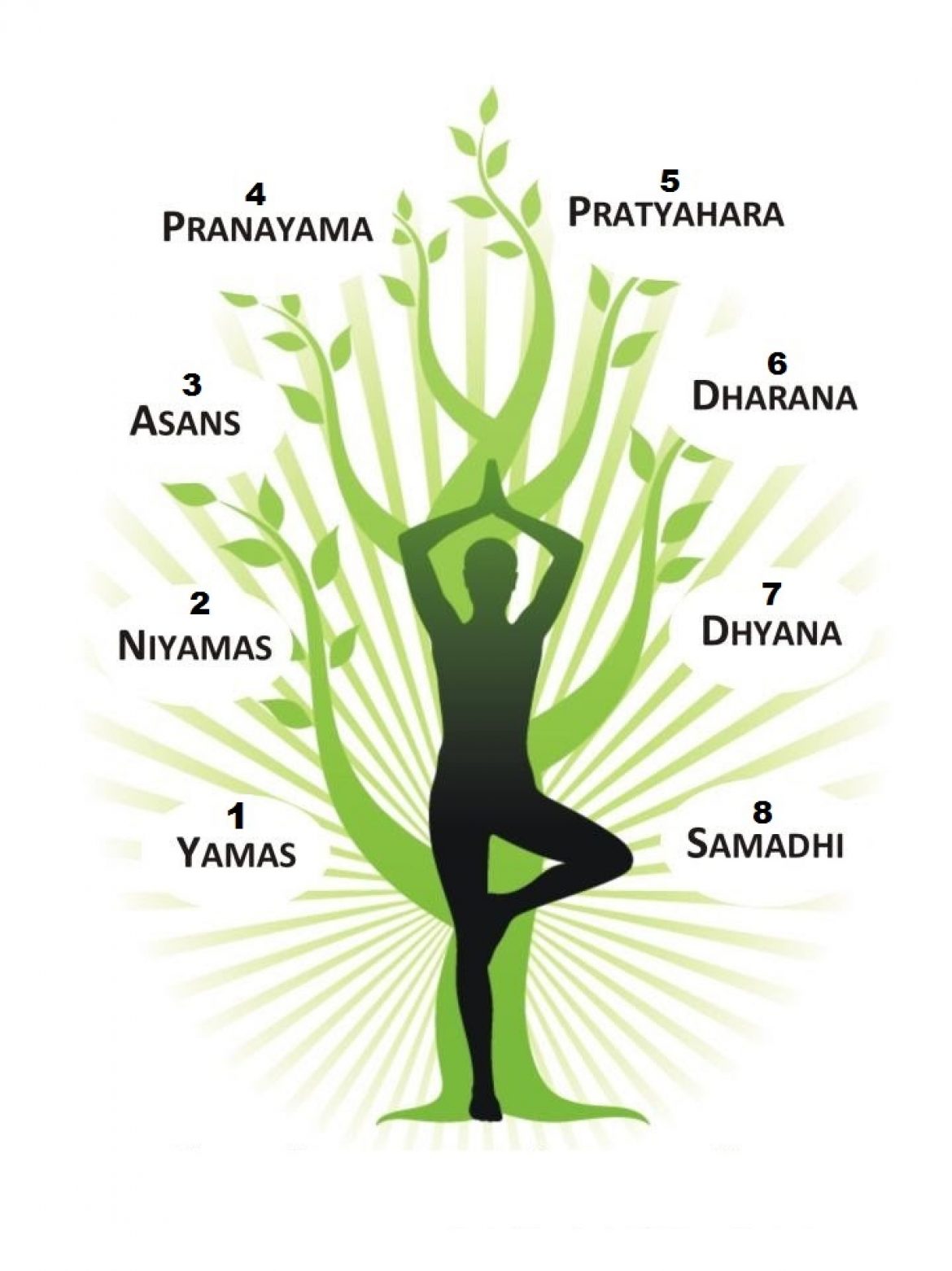

The path of enlightenment, as illustrated by Patanjali, the eminent ancient exponent of classical yoga, provides a deep understanding of yoga in the real sense of it. For the common man on the street, yoga may be associated with stretching, twisting the body into a pretzel and boasting one’s flexibility by performing an array of postures. Unknown to many, yoga is way and beyond all these. As explained succinctly but lucidly by Patanjali, classical yoga comprises eight limbs or paths. They are yama (universal conduct), niyama (individual conduct), asana (posture), pranayama (expansion of life force), prathyahara (withdrawal of senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (liberation).

Yama & Niyama - way of living

Each path is insightful in its own way. For instance, the yamas and niyamas dwell into the dos and don’ts on the path of spirituality. The yamas are subdivided into five fundamental rules i.e. non-violence (ahimsa), non-lying (satya), non-stealing (asteya), non-sensuality (bhramacharya) and non-attachment (aparigraha). Even though these five attributes are preceded with the prefix ‘non’, it does not make them negative in any way. Basically, it implies that once the maya (delusion) is eradicated, the individual becomes benevolent, honest and detached.

On the other hand, the niyamas are classified into the following – cleanliness (saucha), contentment (santosha), austerity (tapas), self-study (swadhyaya) and devotion to the supreme lord (ishwara pranidhana). Not only the yamas, but also the niyamas have to be practiced diligently for one to achieve restful states and greater clarity of mind for a harmonious way of life.

Asana - Sthira & Shukram

The third path, which is the asana, is given lots of prominence in most yoga classes. It is a common sight to see students practise with all their might in order to be able to demonstrate challenging postures. However, it is imperative for the practitioner to be fully aware that these asanas are to be done in a state of “sthira and sukham”, which literally means steadiness and comfort.

The practice of asanas should not condone any form of violence as clearly stated in one of the yamas. Hence, the practitioner must work towards going into the posture, and then holding the posture steadily for a certain duration, and gradually increase it over a period of time. More importantly, the holding of the posture is to be done in sthira and sukham. Ultimately, this serves as a preparatory step for deep meditation. According to Patanjali, the ability to sit still without any movement for several hours is a sign of perfection. Though this state is not unachievable, it may take years for one to attain a state akin to this.

Regular meditation practitioners, who have yet to master a completely still sitting position, will take a longer time to see significant changes in their spiritual journey towards enlightenment. Swami Svatmarama recommends the full lotus posture as a sitting position; however, this pose is notoriously challenging for those whose hip muscles are tight. Hence, it may be more productive to sit in any posture for as long as it is comfortable.

While many are of the notion that one has to practice and perfect the asanas before moving into the practice of meditation, it is merely an assumption.

Undoubtedly, the benefits of doing asanas are manifold. Besides improving flexibility, regular and consistent practice also helps individuals deal with various medical issues such as obesity, cardiovascular diseases, anti-ageing and the list goes on. Also the practice of asanas aids one into the fifth (pratyahara), sixth (concentration) and seventh (meditation) paths in Patanjali’s yoga. Nevertheless, one may embark on any one of these paths directly without going through the asana stage. From a personal point of view, I reckon one will have to practice concentration and meditation with and without doing asana first to experience the impact of the latter.

Pranayama - channel the energy inward

The fourth path in Patanjali’s Yoga is pranayama, which refers to energy control. According to Patanjali, one will be able to achieve energy control by applying various techniques. The common ones include kapalabathi, bhastrika and nadi shodana, with and without kumbhaka (breath retention).

Ultimately, the aim of this practice is to harmonise the energy in the body to a point where its flow is reversed. Instead of flowing outward towards the senses, it flows inward towards the Divine Self that lies in the hearts of all beings.

Only when the energy in the body is directed toward the Self, will one’s awareness be intense enough to penetrate the shrouds of delusion and enter a state of super-consciousness.

It is imperative that the practitioner comprehends the fact that channeling the energy inwardly is the primary step towards divine contemplation. In the practice of asana yoga, it is not uncommon to coordinate breath with every movement.

By and large, all the eight paths in Patanjali’s yoga are interconnected in some way or the other. While some may practise one or two of the paths to achieve enlightenment, novice practitioners would find it useful to mix and match as each and every path complements each other, helping one go into deeper states of relaxation, and eventually attaining a state of one-pointedness.

References:

- Sri Swami Satchiananda. (2012). The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Integral Yoga Publication.

- Swami Muktibodhananda. (2013). Hatha Yoga Pradipika. Bihar School of Yoga.